Strange for Marshall

in Marshall back in 1968:

a Wi-Fi coffee shop where Leonard Baker's Home Electric

used to be—his son now buying a Saturday morning cup there;

a collection of people my Papa might've called hippies

and long-hairs, celebrating and singing themselves;

a steady stream of wheels and jerseys and tight black shorts

that Pat said the sheriff's deputies should wear;

a new bridge across the French Broad, a bridge

without an intersection in the middle;

a high school where the rooms in which we took algebra

and English have been turned into studios for artists;

a bistro in the old Rock Café selling pizza and pasta

and imported beers and good wines;

a courthouse missing a statue of blind Justice,

the statue atop it lost to last winter;

a pirate watching the cyclists, a cell phone talking to one ear,

a live parrot on his shoulder talking to the other;

a small grocery and pub in the old Chevy dealership,

where music is heard every weekend night;

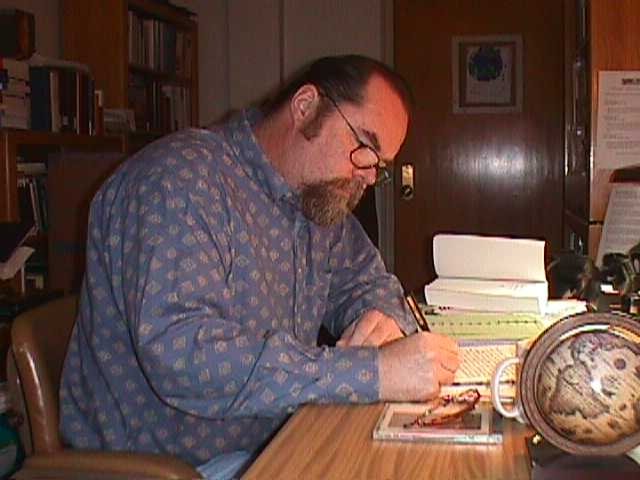

and me—51 years old, big of belly, gray of beard, earringed

and pony-tailed, writing and enjoying a cup

on a sunny October Saturday morning.

Marshall, like so many other Appalachian towns, was dying when I was growing up in the 1960s and '70s. But then something very cool began to happen. A person, or a group of people, in these towns began looking for some way the the place might survive, might not only live but also thrive.

Today Marshall is a mix of old and new. The old hardware is still there, as is Penland's department store. The Home Electric, where my folks bought their appliances, is now Zuma Coffee, and the big building that housed the Chevy dealership is now apartments and a neat grocery store called Good Stuff. When I play there, if I understand it rightly, my stage area (not elevated) is in the garage portion of the place, where the cars and trucks were serviced.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home